(Photo by spatuletail on Shutterstock)

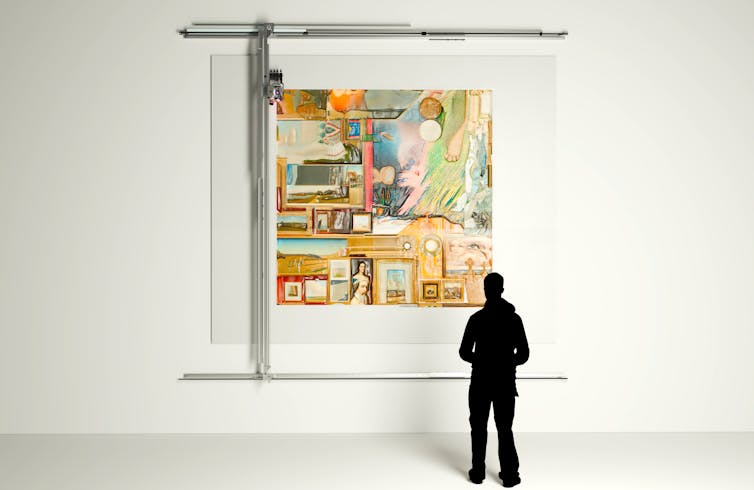

Thirty-four artworks created with artificial intelligence (AI) have gone up for sale at Christie’s in New York, in the famed auction house’s first collection dedicated to AI art.

Christie’s says the collection aims to explore “human agency in the age of AI within fine art,” prompting viewers to question the evolving role of the artist and of creativity.

Questions are not all the collection has prompted: there has also been a backlash. At the time of writing, more than 6,000 artists have signed an open letter calling on Christie’s to cancel the auction.

What’s in the collection?

The Augmented Intelligence collection, up for auction from February 20 to March 5, spans work from early AI art pioneers such as Harold Cohen through to contemporary innovators such as Refik Anadol, Vanessa Rosa and Sougwen Chung.

The showcased pieces vary widely in their use of AI. Some are physical objects, some are digital-only works – sold as non-fungible tokens or NFTs – and others are offered as both digital and physical components together.

Some have a performance aspect, such as Alexander Reben’s Untitled Robot Painting 2025 (to be titled by AI at the conclusion of the sale).

After generating an initial image tile, the work iteratively expands outwards, growing with each new bid in the auction. As the image evolves digitally, it is translated onto a physical canvas by an oil-painting robot. The price estimate for the work ranges from US$100 to US$1.7 million, and at the time of writing the bid sits at US$3,000.

Claims of exploitation

The controversy surrounding this show is not surprising. Debates over the creation of AI art have simmered ever since the technology became widely available in 2022.

The open letter calling for the auction to be canceled argues that many works in the exhibition use “AI models that are known to be trained on copyrighted work without a license.

The letter says: “These models, and the companies behind them, exploit human artists, using their work without permission or payment to build commercial AI products that compete with them.”

The models in question include popular image generators such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and DALL-E.

The letter continues: “[Christie’s] support of these models, and the people who use them, rewards and further incentivizes AI companies’ mass theft of human artists’ work.”

Copyright and cultural appropriation

There are several attempts by artists to bring legal proceedings against AI companies underway. As yet, the key question remains unresolved: by training AI models on existing artworks, do AI models infringe artists’ copyright, or is this a case of fair use?

Artists who are critical of AI are rightly concerned about losing their incomes, or their skills becoming irrelevant or outdated. They are also concerned about losing their creative community – their place in the creative ecosystem.

Last year, Indigenous artists withdrew from a Brisbane art prize, highlighting concerns about AI and cultural appropriation.

At the same time, many AI artists don’t use copyrighted material. Refik Anadol, for instance, has stated that his work in the Christie’s collection was made using publicly available datasets from NASA.

How the ‘work’ of art is changing

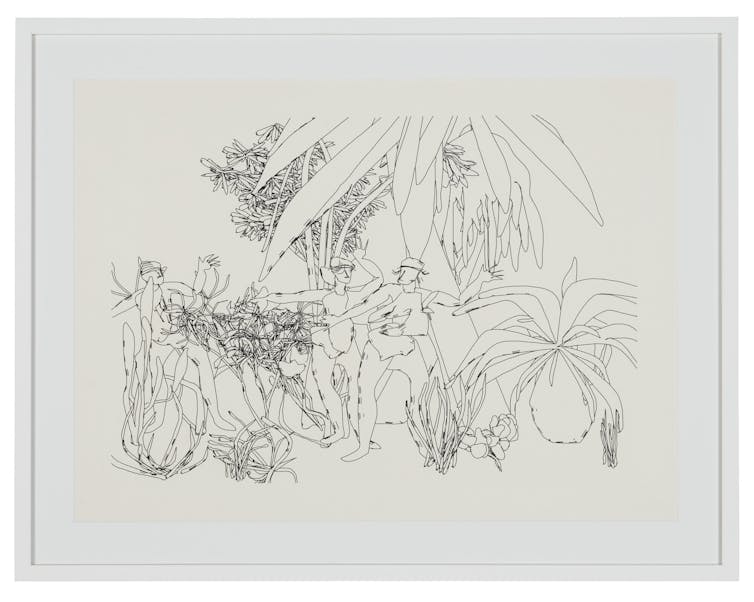

The Christie’s event occurs during a major shift in what it means to be an artist, and to be creative. Some participants in the show even question whether the label of “artist” is even necessary or required to make meaningful imagery and artifacts.

Many non-artists may wonder – if AI is used, where is the real “work” of art? The answer is that many forms of work will look different in the age of AI, and creative endeavors are no exception.

Creativity gave humans an evolutionary edge. What happens if society censors or undermines certain forms of creativity?

Clinging to traditional ideas about how things are done ignores the bigger picture. When used thoughtfully, technology can stretch our creative potential.

And AI cannot make art without human artists. Creating with new technologies requires context, direction, meaning, and an aesthetic sense.

In the case of the Christie’s auction, artists are doing much more than typing in prompts. They iterate with data, refine models, and actively shape the end result.

This evolving relationship between humans and machines reframes the creative process, with AI becoming more like a “conversational partner.”

What now?

Calling for the Christie’s auction to be canceled may be shortsighted. It oversimplifies a complex issue and sidesteps deeper questions about how we should think about authorship, what authenticity means, and the evolving relationship between artists and the tools they use.

Whether we embrace or resist AI art, the Christie’s auction pushes us to rethink artistic labor and the creative process.

At the same time, Christie’s may need to take more care to produce collections that are sensitive to contemporary issues. Artists have real concerns about loss of work and income. A “move fast and break things” approach feels ill-suited to the thoughtfulness associated with artistic production.

Beyond protest, more education and collaboration is required overall. Artists who do not adapt to new technologies and ways of creating may be left behind.

Equally important is ensuring AI does not diminish human agency or exploit creatives. Discussions around achieving sustainable and inclusive AI could follow other sectors focusing on equally sharing benefits and having rigorous ethical standards.

Examples might come from the open source community (and organizations such as the Open Source Initiative), where licensing and frameworks allow contributors to benefit from collective development. And in the tech realm, some software companies (such as IBM) do stand out for their rigorous approach to ethics.

Rather than canceling the Christie’s auction, perhaps this is a moment for us to reimagine how we do creativity and adapt with AI. But are artists – and audiences – prepared for a future where the nature of being an artist, and creativity itself, is radically different?

Jessica Herrington, Futures Specialist, School of Cybernetics, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Where is the mastery of the craft? To me that is the singular aspect of a truly great piece of art: it displays the artist’s discipline and absolute control over their chosen media; from concept to execution the resultant piece reveals the artist’s approach, unique POV and techniques utilized as the work progresses and evolves. Mainly, it is the artist’s emotional response to the world around them at that specific time in their life. It is their thoughts on display; it is through their skill how those thoughts elicit the a response from the viewer. A unique product born from a unique mind.